Food Economics

Why Food Is So Expensive in Australia (And Where the Money Actually Goes)

Food prices in Australia feel out of control.

Groceries cost more every week. A casual takeaway can easily push past $30. Eating out, once routine for many households, now feels like an occasional indulgence. At the same time, food businesses keep saying they are struggling to survive.

If food is so expensive, why does no one seem to be making much money?

The answer isn’t greed, incompetence, or a single bad actor. It’s structural. Australia has built a food system that is inherently expensive to operate, and prices are now catching up to that reality.

This article explains why food is so expensive in Australia, and where your food dollar actually goes.

Australia Starts With a High Cost Base

Before a single ingredient is grown, processed, or cooked, Australia is already an expensive place to run a food business.

This isn’t just a feeling. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Consumer Price Index, food and non-alcoholic beverage prices have risen materially in recent years, contributing directly to Australia’s overall inflation rate.

Food prices don’t rise in isolation. They reflect the cost structure of the economy underneath them.

Australia has:

- High minimum wages and strong penalty rates

- Expensive commercial rent

- Long, fuel-intensive supply chains

- High energy costs

- Heavy compliance, insurance, and safety requirements

These are not temporary shocks. They are structural features of operating in Australia.

Food businesses don’t get to opt out of them.

Labour Is the Dominant Cost

Food is labour-intensive at every step:

- Farming and harvesting

- Processing and manufacturing

- Transport and warehousing

- Retail and hospitality

- Cleaning, compliance, and waste handling

In Australia, a casual hospitality worker can cost roughly $30–$38 per hour once loadings and on-costs are included. Weekend and public holiday rates push that even higher.

Unlike manufacturing or software, most food labour cannot be automated away. Someone still has to prep, cook, stock, serve, clean, and deliver.

When labour costs rise across the economy, food prices don’t have many options but to follow.

Supermarkets Are Powerful, Not Excessively Profitable

Supermarkets are often blamed first when food prices rise. They are highly visible, highly concentrated, and clearly influential.

But influence does not automatically mean high profit.

Australian supermarkets operate on very thin net margins, typically around 2–3 percent. On a $100 grocery shop, that translates to roughly $2–$3 in profit.

The rest of the money is absorbed by:

- Farmers and manufacturers

- Transport and distribution

- Store and warehouse labour

- Rent, refrigeration, and energy

- Theft, spoilage, and waste

Supermarkets are extremely efficient operators. Efficiency, however, does not make food cheap. It simply keeps the system functioning at scale.

Australia’s wages, distances, and energy costs mean even the most optimised retailers remain high-cost businesses.

Distance Acts Like a Hidden Tax on Food

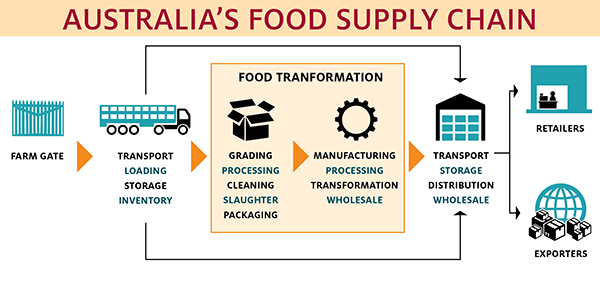

Source: Australian Government, ABARES

Australia’s food system is expensive long before food reaches a supermarket shelf.

As the supply chain diagram shows, food in Australia rarely moves in a straight line from farm to consumer. It passes through multiple stages — production, aggregation, processing, distribution, and retail — often separated by hundreds or thousands of kilometres.

Each of those steps adds cost.

Food grown in regional Australia must be:

- Collected and aggregated

- Transported to processing facilities

- Stored, often under refrigeration

- Moved through one or more distribution centres

- Transported again to retail outlets

None of this is inefficient by accident. It is how risk is managed in a large, sparsely populated country. But every hand-off adds labour, fuel, energy, handling time, and spoilage risk.

In denser countries, supply chains benefit from proximity. Trucks can make multiple short drops in a single run. Processing facilities sit closer to population centres. Storage times are shorter.

Australia doesn’t have that advantage.

Distance acts like a structural tax on food. It raises costs quietly and consistently, regardless of how well individual businesses are run.

This is why food prices don’t fall quickly when input costs ease. Once logistics, infrastructure, and distribution networks are built around long distances, those costs become permanent features of the system.

When Australians pay more for food, a significant portion isn’t going to profit. It’s paying for the geography that sits between where food is produced and where it’s eaten.

Convenience Is the Fastest-Growing Cost Driver

Groceries have become more expensive. Convenience food has become significantly more expensive.

That’s because convenience doesn’t remove costs from the food system — it adds new ones around it.

Food delivery platforms changed expectations about speed and availability, but they didn’t change the underlying economics of food. Every delivered meal now carries additional layers that simply don’t exist in dine-in or home cooking.

A typical delivery order includes:

- Platform commissions of 25–35 percent

- Delivery and service fees

- Higher menu prices to offset margin loss

- Extra packaging designed for transport

- Additional kitchen labour per order

None of these costs improve the food itself. They improve access, speed, and reliability — and those benefits are paid for by the customer.

For restaurants, delivery rarely improves margins on its own. Most venues that make delivery work do so by deliberately changing menus, pricing, and kitchen operations to compensate for platform fees — something we break down in detail in our guide on how to increase food delivery sales for your restaurant.

The result is that convenience food feels disproportionately expensive. That’s not because restaurants are suddenly charging more for the same meal. It’s because the system delivering that meal has become more complex, more fragmented, and more costly to operate.

Convenience doesn’t make food cheaper.

It makes food available, and availability comes at a price..

Restaurants Are Raising Prices Just to Stand Still

Higher menu prices don’t mean restaurants are doing well.

Since 2020, restaurants have faced:

- Ingredient cost increases of 20–40 percent

- Labour cost increases of 15–30 percent

- Higher rent pressure

- Rising energy bills

- Higher insurance premiums

- Delivery cannibalising dine-in margins

Even well-run venues typically aim for net profits of 5–10 percent. Many now operate closer to 2–3 percent, and plenty operate at a loss.

Price rises often lag cost increases. When menus finally change, it feels sudden, but it is usually overdue.

Higher prices often mean survival, not success.

Packaging, Waste, and Compliance Are Built In

Modern food systems prioritise safety, consistency, and traceability. Those priorities add cost.

Every meal now carries:

- Single-use packaging

- Labelling requirements

- Food safety systems

- Audit costs

- Temperature controls

- Overproduction buffers

Waste is unavoidable. Supermarkets expect a level of spoilage. Restaurants over-prepare to avoid running out. Delivery requires sturdier packaging.

Waste rarely appears on receipts, but it is built into prices.

Australians Want Conflicting Outcomes

Australians want:

- Affordable food

- High wages

- Fair farmer pay

- Strong food safety

- High animal welfare standards

- Convenience and speed

- Wide choice

These goals conflict.

You cannot combine high wages, long distances, heavy regulation, and instant convenience with low prices without someone absorbing the cost.

Right now, that cost shows up at the checkout.

Where the Money Actually Goes

A simplified breakdown of a $25 takeaway meal looks roughly like this:

- Ingredients: $7–9

- Labour: $6–8

- Rent and utilities: $3–4

- Platforms and marketing: $4–6

- Packaging and waste: about $2

- Profit: $0–2

There is no hidden surplus. Profit is what remains after the system is paid for.

The Real Reason Food Feels Expensive

Food in Australia feels expensive because the system delivering it is expensive.

High wages are unavoidable. Distance increases logistics costs. Convenience adds layers rather than efficiency. Waste is structural. Margins remain thin.

The real question is not why food costs so much now.

It is why Australians expected food to remain cheap in a country that is expensive to operate in.

Final Takeaway

Australia has not built a cheap food system.

It has built a safe, regulated, labour-heavy, convenience-driven food system. Those systems cost money.

Most of what consumers pay goes toward keeping that system functioning, not enriching any single participant.

Food is not expensive because someone is pocketing the difference.

It is expensive because this is what food actually costs in Australia.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login